A home datacenter

Quick context: I have been in IT for ~25 years, working across backend, SRE, clouds, and capacity/scaling. This series is a practical project running in my own datacenter, not a resume exercise.

In my home datacenter (not to confuse with a homelab; I host here too many important services to call it a homelab) I have roughly 12-15 small boxes running. This number fluctuates: sometimes I add a new node, sometimes one dies and gets replaced.

It is a bare-metal Kubernetes cluster deployed on HP T620 / T630 thin clients. Three nodes run the control plane, and the remaining 9-12 are workers.

Turning off nodes to save a bit of energy

At some point I realized the overall usage was low: around 20% memory and ~15% CPU. This happened after I removed a few heavier deployments (Mastodon with its Postgres and Redis, my own Elasticsearch stack, a 5-node Cassandra cluster, and Longhorn). So I logged into a few workers, cordoned and drained them, then powered them off with systemctl poweroff.

The goal was simple: save a bit of energy. These boxes draw around 13W on average, so powering off 5 of them is only a couple of EUR per month, but it still felt worth it.

Weird loadAvg behavior

Later, I started deploying new services, and the cluster began to feel worse again. What surprised me was that CPU and memory still looked underutilized, yet nodes had high load averages. In practice, this correlated with workloads that were heavy on disk I/O or had a lot of waiting on the network: the machines were not busy in the CPU sense, but they were definitely not idle either.

Quick reminder: load average is not "CPU usage". It is a signal of how much work is waiting to run, including tasks stuck in uninterruptible I/O.

First attempt: Kubernetes Descheduler

My first attempt to fix this was Kubernetes Descheduler. I configured it to rebalance workloads across nodes so the cluster would be more evenly loaded. (Important warning: a lot of descheduler decisions are based on pod requests and limits rather than real-time usage, so it is not a perfect proxy for "actual load", but it still helped for a while.)

It did not take long until load averages spiked again. This tended to happen when some heavier pods landed on nodes that were already experiencing a lot of contention (context switching and/or I/O wait).

The minimum stable cluster size

Eventually I concluded there was a minimum number of worker nodes that my cluster needed to stay stable. At that time, it was five. That made me ask the obvious question: could Kubernetes Cluster Autoscaler help here? Could I configure it to dynamically resize a bare-metal cluster?

Why not the upstream Cluster Autoscaler

After a quick deep dive, I learned that Cluster Autoscaler is built around scaling pre-configured node groups through an infrastructure provider integration. On public clouds, that typically means increasing or decreasing the size of an autoscaling group, and scale-down usually maps to terminating instances via the provider API. Moreover, "stop the node so it can be quickly reused later" is not a standard Cluster Autoscaler workflow.

On bare metal, this is not impossible, but it is not something you get out of the box. You would need an integration that looks like "a provider" to Cluster Autoscaler and can reliably power machines on and off, manage groups, and handle edge cases.

A short rabbit hole (aka brainstorm)

I still decided to give it a try. I started sketching a virtual node group and a virtual "cloud provider" for my setup. The first commits were mostly me pulling in Cluster Autoscaler packages and exploring how far I could take this approach.

At some point, the amount of compromise (and glue code) stopped making sense for my constraints. But that rabbit hole produced plenty of interesting questions, and I wrote them down as potential directions:

- What if scaling decisions were not based only on CPU and memory, but also on load average or other contention signals? Load average is noisy and context-dependent, but in my setup it seemed meaningful.

- What if strategies were pluggable and chainable? For example, first check the load average, then fall back to CPU/memory, and then add custom rules.

- How should the system react to scheduling signals like "pod cannot be scheduled due to insufficient resources"?

- Could a lightweight metrics collector (maybe eBPF-based) provide better node signals than a heavier stack?

- What if "power on" was pluggable: Wake-on-LAN, IPMI, perhaps later something else?

- Should this be implemented with a classic reconciliation loop design?

- If yes, what comes first: scale down or scale up?

- Should scale-down be modeled as a state machine (cordon, drain, verify, power off, cooldown)?

The birth of the Cluster Bare Autoscaler

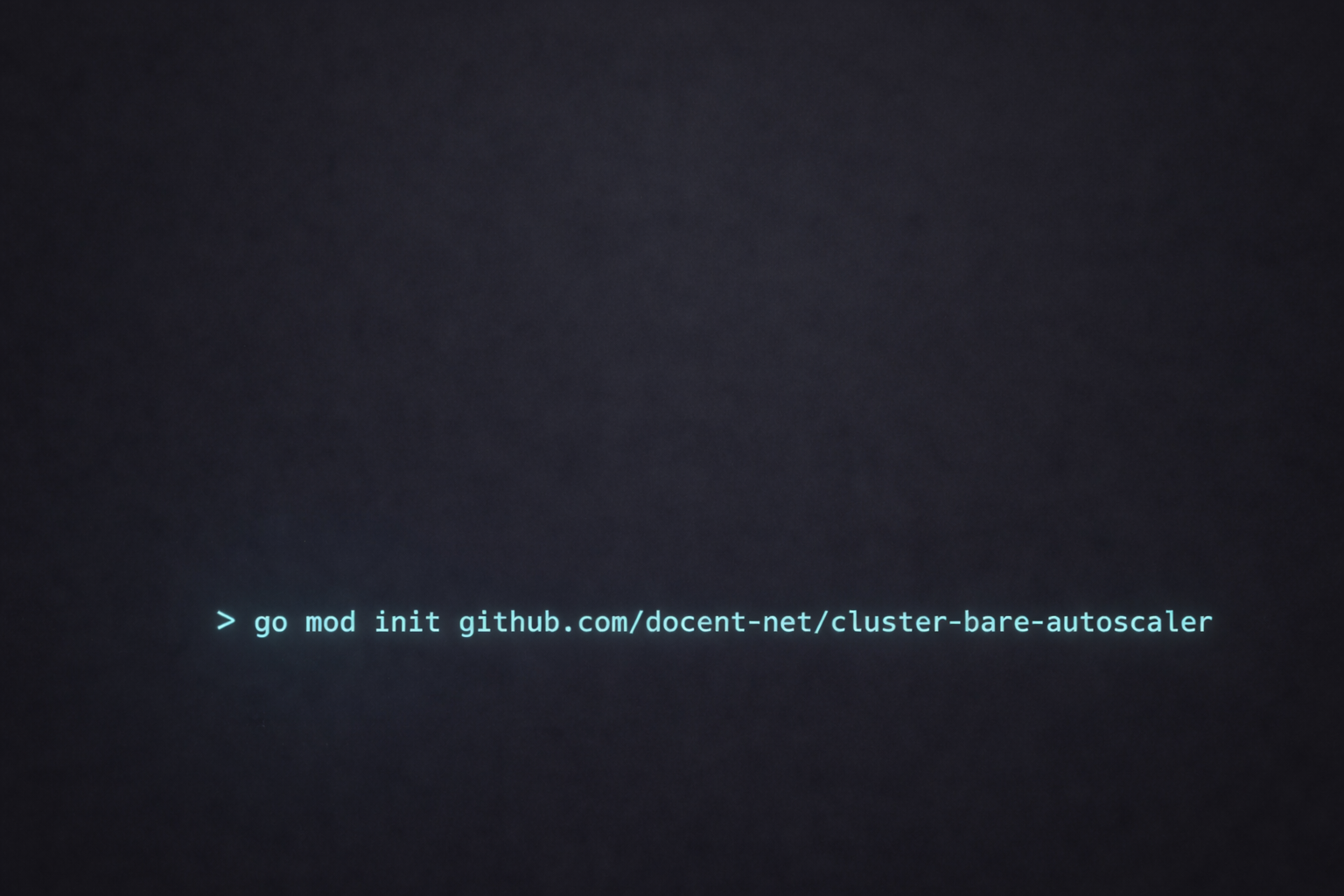

So I did the obvious thing and decided to build my own autoscaler—designed specifically for bare-metal servers. Obviously, this is niche: self-hosting is already a niche, Kubernetes is a niche within that, and "a cluster big enough to benefit from dynamic scaling" is even smaller. There might only be a few of us using it. Still, I think it is a problem worth solving.

This is how Cluster Bare Autoscaler was born, and it is also the beginning of the story I will be posting here, along with the project’s evolution.

The project today (and how to get involved)

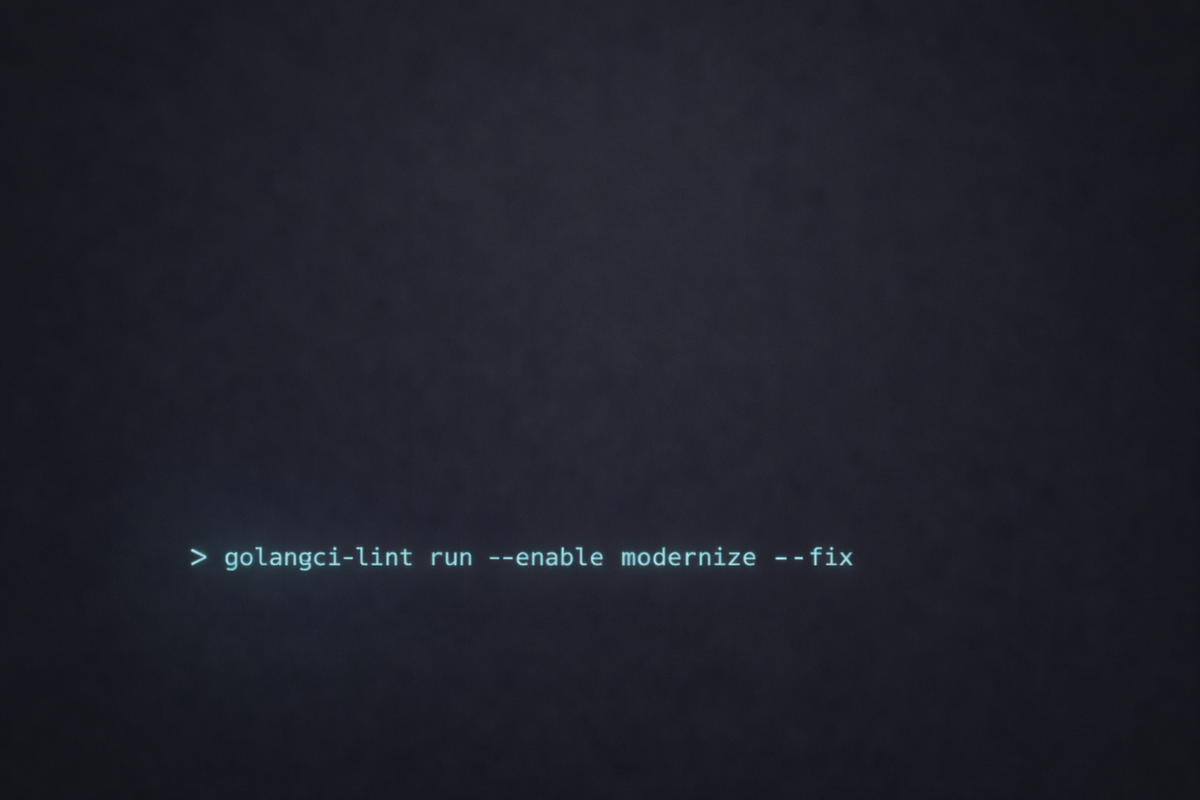

Cluster Bare Autoscaler is already around 10 months old and has been running in my datacenter throughout this time. It already provides a solid set of features, including dynamic scaling based on load average, enforcing a minimum node count, resource-aware decisions (how many resources are required to keep the cluster safe), Wake-on-LAN power-on, and more.

If you want to try it, go ahead: https://github.com/docent-net/cluster-bare-autoscaler

I decided to create this blog series to explain the design decisions behind CBA, share lessons learned (including the mistakes), and document the open questions and ideas for the future.

If you feel like supporting me on this voyage, there are plenty of GitHub issues to pick up. You can also start a new discussion to talk about anything related to CBA—questions, ideas, edge cases, or your own bare-metal scaling stories.

A bit about me

I have been working in IT for about 25 years. I started back in the pre-cloud and pre-containers era as a backend engineer (PERL anyone?), then spent years migrating workloads into virtualization, cloud, and finally Kubernetes. Over that time I have worked hands-on with all major cloud providers, built and operated large-scale systems, and spent a good chunk of my career in capacity-related teams - dealing with scaling problems, quota constraints, and the practical reality of keeping platforms stable under changing demand.

I have also helped build internal cloud platforms from the ground up, including the less glamorous parts like capacity planning, forecasting, and making sure scaling mechanisms do not collapse under real production behavior. Oh—and bare-metal activities included.

These days I work primarily as an SRE, but very much on the border of backend engineering: I build services, but I also care deeply about operability, reliability, performance under load, observability, and the automation around scaling and incident prevention.

So this blog series is not a resume project or a "hello world" experiment. It is a practical tool I built for my infrastructure, and I am sharing the reasoning, tradeoffs, lessons learned, and open questions as the project evolves.